How the Reflow project turns Amsterdaminto Europe’s testing ground for textile circularity

“Lompenboer!” is a shout that any Dutch person who grew up in the 1960s recognizes very well. It announced a ragman arriving at a neighbourhood square. His job was to collect old textiles and carry them on his bakfiets (carrier bike) to a sorting point, where they would be turned into, for example, isolation materials, cleaning cloths, or even new garments with a special label. This system ensured that there was no textile spillage, that many job opportunities around recycling textiles existed, and, above all, that youngsters who brought the textile to the ragman could buy themselves firecrackers. “At least that’s what I did”, Ger Brinks, CEO of BMA Techne, business technology management firm, smiles. The Reflow project aims to revive the spirit of the ragman. Financed by the EU as part of the Horizon2020 initiative, Reflow brings together BMA Techne, the Amsterdam Municipality, technological think tank Waag, and cultural organization Pakhuis de Zwijger. The partners test and develop techniques for the circular use of textiles so that Amsterdam decreases the number of virgin fibres it uses.

A methodology for circularity

Reflow is a three-year project engaging 26 partners in six different European cities. Through their pilot programs, the cities explore the circular economy in four “challenge dimensions”: material streams and flows, governance, people and businesses, and technology. The aim is to see how those cities can reach the circular economy and to combine the findings into an open-source methodology. The project’s scope is diverse: Paris experiments with tackling event waste; Cluj-Napoca in Romania practices urban energy monitoring; Milan deals with sustainability of food marketplaces; Berlin aims to put waste heat back into use; Vejle in Denmark designs solutions to plastic waste; and, finally, Amsterdam focuses on improving textile circularity. The pilot cities hold monthly talks where partners exchange experiences and knowledge. “We work at different speeds, but we help each other with tips, exchanging how we can do things differently,” Cecilia Raspanti, Waag’s fashion designer and co-founder of TextileLab Amsterdam, adds.

The Amsterdam pilot was lucky to tap into the wealth of already existing initiatives that tackle textile circularity. The city regards itself as an important textile designer and a jeans capital of Europe. “Reflow is a connector of everything that’s already happening in the city”, Ista Boszhard, a fashion designer at Waag and co-founder of TextileLab Amsterdam, points out. Subsequently, the pilot’s goal is to strengthen the circular model by developing tangible, open-source tools. To do so efficiently, Reflow partners needed to understand Amsterdam’s existing textile landscape.

Listening to the city

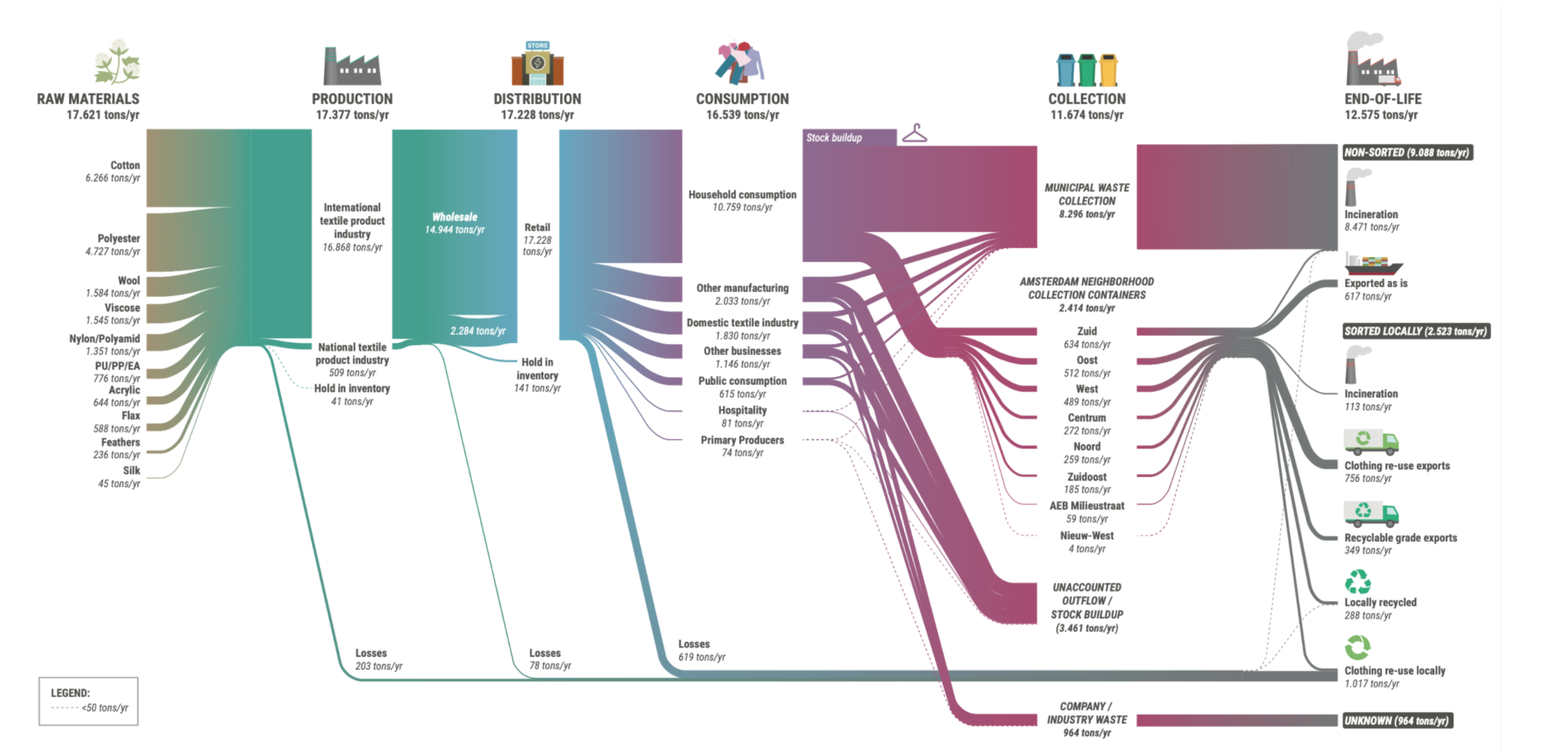

The first stage of the pilot involved discovering what’s already happening and, subsequently, engaging stakeholders to deepen their participation in every step of textiles’ life-cycle. Complex systems are easier understood when mapped out, so Reflow Amsterdam partnered with Metabolic, a sustainability consultancy distinguished by its systems thinking approach. The consultancy created a graph of Amsterdam’s textile waste streams. The municipality supported the mapping process with its research. Already at this stage, some crucial findings emerged. For example, textiles in Amsterdam are often not discarded properly. “They end up in a normal bin while they could feed back into the circular model,” Boszhard points out.

To deepen their understanding of what industry insiders need, Reflow also engaged in more bottom-up research. During “Monday laundry days”, organized by Amsterdam Economy Board and Reflow in September, various textile actors came together and spoke about the obstacles on their journey towards circularity. The meetings sparked an investigation into an innovation lab, where Reflow and partners will test what they can do with discarded textiles – this counts for clothes, but also “everything else used in homes, hotels, and hospitals”, Brinks highlights. “To achieve significant improvements in textile recycling, we need spinning capacity,” he adds. Currently, the recycling focus lies in mono-streams but Reflow wants to explore the possibilities of recycling textile blends.

The Metropole Region of Amsterdam,which consists of 32 regional municipalities, is bringing together the needs, existing systems, and networks together in a soon-to-be-published collaborative roadmap and vision. The roadmap connects the whole supply chain, from textile collectors to makers that use recycled fabrics. Bringing networks together will “create enough momentum to break with the old habits,” Raspanti hopes. “If it comes from all sides, we can get there. This way, it’s much more long-term and sustainable, because it’s not carried by a few but by many.” Its holistic approach makes Reflow stand out among sustainability projects, which usually have a singular focus. “The circular economy is only happening when we do it together –citizens, businesses, no matter what your job is, you’re connected to the city and involved in this supply chain,” Raspanti points out.

Engaging every stakeholder

Reflow’s holistic approach is visible not only in its research but also in the action plan. Its activities stretch from political, industrial, to citizen-level interventions. Subsequently, Reflow’s scope is simultaneously systemic and tangible.

“Government organizations play a dominant role in lowering barriers for the introduction of material recycling”, Brinks points out. Therefore, Roosmarie Ruigrok, founder of Clean & Unique and a project coordinator from the Amsterdam Municipality, lobbies in different Amsterdam areas as part of Reflow. Since each part has its budget, some are more dedicated to the circular economy than others. Ruigrok tries to level the playing field by pushing initiatives from one area to another. “Municipality regards it as important to be part of Reflow as now we can find out what’s working and what’s not,” she explains.

Fresh solutions are greatly needed, especially with the collapse of the second-hand market. In the past, tender-winning companies would sort out the city’s textile waste, re-sell wearables, and burn non-wearables. Such an arrangement was only workable when wearables made enough profit to justify the destruction of other products. Today, however, “there’s too much, and the quality is too low”, Ruigrok states. Subsequently, the market needs another value proposition. Such a transformation supports the city’s plans to halve its use of primary raw materials by 2030 and become fully circular by 2050.

Industry insiders welcome Reflow’s plans, as they support them in developing circular business models and the day-to-day processes. Reflow is particularly interested in the way in which technology can play a part in the circular transition. For the Amsterdam pilot, the goal is to bring supply and demand closer together. The partners are working on creating an exchange system platform that would connect circular textile makers to various parts of the supply chain. “We expect to see software development within the next 1.5 years,” Raspanti explains. “Then, we can start seeing the first outputs and speculate on how we can use them.” The three-year length of the program leaves room for experimentation and adjustments.

Sharing and creating best practices

The technological focus also allows for merging digital solutions with the good old concept of a ragman in a spin-off project called, DLT4U. The partners plan to create an application that facilitates textile collection. Upon delivery, citizens receive points that they can exchange in various spots across the city. “DLT4U can tackle many different problems, from creating a marketplace that works for the citizens to allowing us to track how resources move around the city,” Raspanti states.

The app, however, can only be rolled out once the COVID-19 pandemic calms down. Meanwhile, Reflow is working on an open-source booklet that explains textile circularity in 16 steps, corresponding to the Amsterdam Circular Textile Wheel. The publication will offer concrete actions to deal with each step and be useful for designers, fashion insiders, and educators alike. The weekly, chapter-by-chapter release started on February 16th on Reflow and Waag’s websites.

Amsterdamers can also expect to see an awareness campaign in the months to come. “We want to inform consumers about the zero-waste motto. Reduce, rethink, repair, repurpose. Recycle is only the last stage,” Ruigrok explains. “We don’t want people to trash, but if they do, they should at least do it properly,” Boszhard adds. The campaign will aim at improving our consumer habits in ways that are sometimes very small and surprising. “One thing people need to understand as soon as possible,”Raspanti states laughingly, “Is that they need to tie their shoes together when they put them in a clothing container.” Her request appears very reasonable once it’s clear that the value of a pair of shoes increases 40-fold as compared to a loose shoe.

Turning a crisis into an opportunity

For a reason, all too painfully obvious, many planned activities, including workshops, had to move online. Yet Amsterdam partners feel that overall, the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t disturb Reflow too significantly. It did, on the contrary, highlight how misplaced the predominant fashion business models are, showing the relevance of Reflow’s work.

Although visits to other cities need to be postponed, the collaboration continues on a European scale as well. “We’re extremely proud to see how the cities approached COVID and the flexibility of the local teams,” Raspanti states, evoking online workshops organized with the support of an online software Miro. “It’s impressive how pilots’ local teams took the challenge head-on and managed fine until now.” The partners from around Europe worked together to align how to best benefit from the changed circumstances. “For example, we had a whole discussion on where to put information about textile recycling,” Raspanti recalls. “We came up with spots like a trash bin, a pharmacy, and a supermarket. Because that’s all where people go now, and we have to work with it”. COVID also inspired the Amsterdam pilot to explore creating a reusable isolation coat. The sub-project aims to investigate whether a reusable coat is doable, how to wash it, and what kind of laundry machine they would need, in collaboration with the healthcare sector.

Powering networks

Reflow has so far enjoyed a widespread interest from the Dutch textile world. Industry insiders from all over the Netherlands joined their events, both online and the scarce offline ones. “We’re a nucleus that helps the development of textile recycling in other parts of the country,” Ruigrok tells. The partners welcome the growing interest in networked interactions. “The start-ups or innovators would usually come to the municipality to request some funding, but now it’s more common to see them ask about networks in their field. They want to see who’s there and grow together,and that’s a marvellous development,”Ruigrok lauds. For the 2 years until the project’s completion, Reflow will continue to connect stakeholders in a well-thought-out and all-encompassing effort to make circular textiles a reality.

Online events by Reflow pilot partner Pakhuis de Zwijger can be found at https://dezwijger.nl/programmareeks/reflow/

For more information

- culture.fashion

- reflowproject.eu

- zuzanazaruk.com